Why are the César Manrique toilets works of art?

28/06/2017

Violeta Izquierdo: “César Manrique did not view toilets as secondary spaces; instead, he gave them artistic value.”

They say that to truly know a person, you must enter their toilet. Today, we explore César Manrique’s: beautiful and surprising, functional and highly refreshing. Art historian Violeta Izquierdo guides us through this journey into the drains of the Lanzarote genius.

We know we’re facing a Manrique toilet when visitors line up at the toilets of the Cactus Garden, Jameos del Agua, Castillo de San José, among others, to take photos and comment, somewhat embarrassed, on the sexual drawings on the doors. Why do they captivate us so much? Are his toilets artistic?

We discussed these questions with Violeta Izquierdo, Associate Professor of Contemporary Art at the Complutense University of Madrid and author of the doctoral thesis “The Artistic Work of César Manrique,” for which she received the Cum Laude distinction in 1996.

César frequently worked with materials such as volcanic stone, glass, wood, and recycled local objects. His toilets replicate this approach. Was it a formal, purely aesthetic search, or is there also a discourse, a semantic intention?

César Manrique focused on what was closest and most immediate to him: the place where he lived, its traditional architectures, and its natural values. Concerned with environmental issues, he acted without causing destruction and drew from natural resources, giving them new meaning. He understood the uniqueness of the place and created an architecture that respected the past.

César Manrique integrates the architecture of Lanzarote.

To decorate the spaces with all these details, he never resorted to specialized stores. Instead, he himself, through various objects, created what he needed, such as lamps made from boat buoys or plant pots made from old watering troughs or distilleries. He paid special attention to harmonizing the ornamentation of the details with their context, so that what usually goes unnoticed due to its lack of interest becomes part of his ensembles with renewed appeal. He succeeded in combining the artificial with the natural, what was created by man with what nature provided. His toilets are an excellent example of the fusion between the functional and the aesthetic, creating comfort and the best conditions for life to develop both inside and outside the building.

There are four components in nature: water, earth, fire, and air, which, when united, are the cause of life on our planet. These create the animal and plant world. When Manrique uses water, vegetation, or rocks in his spaces, he seeks a sincere connection with nature. Ornamentation through natural elements generates a positive effect on humans, as by presenting them harmoniously, he ensures they become an inseparable part of their lives.

The toilet has traditionally been an intimate space, physically and visually enclosed to provide privacy for its users. However, it is common for César to break these boundaries, either by incorporating windows that connect the interior with the exterior or skylights that expand the space upwards. Can you help us understand the reasons behind this architectural decision?

César Manrique’s overflowing imagination

If there is anything that justifies the fertility of Manrique’s artistic career, it is the overflowing imagination that accompanied the artist throughout his life. Through imagination, Manrique nourished the roots of his creative thinking, drawing this strength from two main sources of inspiration: direct perception and intuition.

Many times we don’t realize it, but whether something in a building moves us or leaves us indifferent depends on the degree of imagination the artist has employed in it. This also leads us to think that this initial instinct or intuition is often strongly fueled by an aesthetic impulse, which in Manrique was openly manifested in all his creations.

In the ornamental aspect, he played with the intersection of different materials (volcanic walls, wood), considered the visual elements of the landscape (color, line, scale, shape, texture, space), and never overlooked the natural resources that promote life and growth: water and plants. In some of his creations, the building and the garden become one. It is difficult to determine where one begins and the other ends, as both intertwine, mutually providing what they need.

César Manrique did not view toilets as secondary spaces; instead, he elevated them to artistic status, integrating them into the stone structure. He blended the whiteness of marble with the blackness of lava, and large windows introduced a touch of greenery through the exterior gardens.

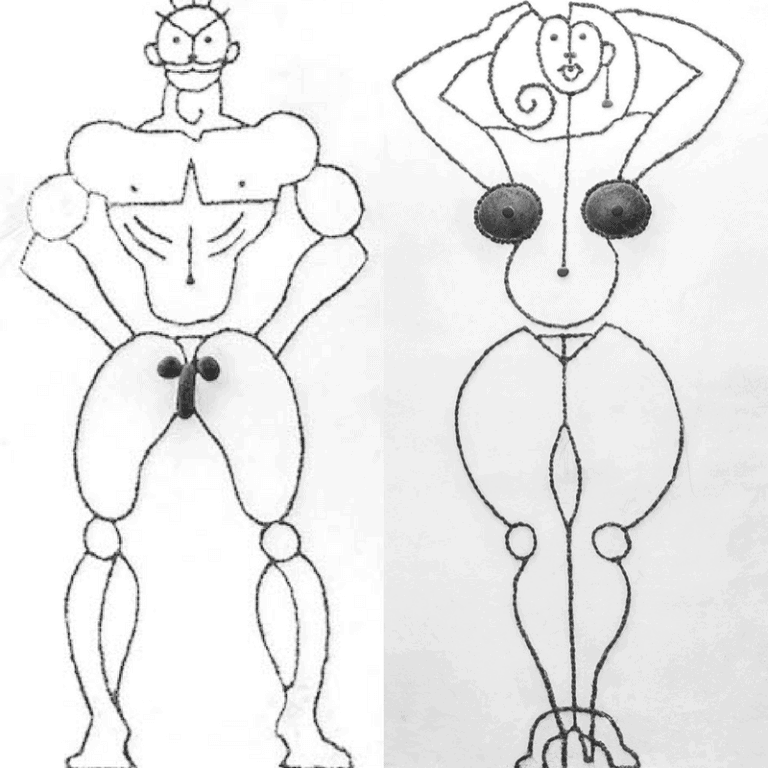

His toilets are guarded at the entrance by drawings of human figures, whose external genitalia—vagina, breasts, penis—are depicted in a grotesque manner, with materials and sizes deliberately disproportionate to the rest of the body. Moreover, he emphasizes this division of sexes with the categories of male and female. What worldview of sexuality might the artist be expressing with his toilets?

The familiar world of detail affects the overall appearance, and this is something Manrique knew very well. When conceiving a work, he thought of its smallest details, never leaving them to chance. For him, everything was important: streetlights, railings, doors, trash bins, benches, floor texture, types of plants, the shape of the curb, even the stone placed seemingly casually at the bottom of a pool.

The signage used in the toilet is another unique way of differentiating the space it refers to and clearly differs from the usual iconography typically used. These creative drawings or designs that differentiate the women’s or men’s toilets (originally and unusually named as male and female) aim not to repeat common stereotypes, but to facilitate quick identification of these spaces by users, while adding the aesthetic nuance that the artist always infused into his creations.

Symbolism in the Jardín de Cactus toilets

In these representations (which we can find, for example, in the toilets of the Jardín de Cactus), we observe a certain primitivism. Was the artist alluding to Canary Island indigenous art? What movements influenced his way of representing the human body?

During his learning period (1942-1950), he was heavily influenced by Canary Island art. Later, in Madrid, he entered a phase of experimentation (1950-1957), influenced by artistic avant-gardes and his entry into informalism (1958-1970). As a painter, César Manrique skillfully combined with extreme sensitivity what belonged to him as a native of Lanzarote, that is, the texture, color, and other characteristics of his land’s geography and geology, with an abstract-informal language based on the expressiveness of the pictorial material.

From a personal artistic approach, he suggests rough surfaces or those of volcanic magma, gradually delving into the mystery and depths of his town to uncover and bring to light, through various geological, zoomorphic, or biomorphic processes, what was hidden beneath the earth. His early creations are a tribute to the untamed, an expression of the primal. As we approach, we notice those folds, those wrinkles marking the surface, resembling delicate skin, which gradually became covered with the ashes and dust of ancient eruptions. Manrique identified his painting with all the characteristics of the most rigorous modernity, while also feeling emotionally connected to the most ancestral aspects of our human condition.

Art in the Toilets of the MIAC – Castillo de San José

A constant in the work of the Canarian artist is spatial continuity and the artificial-natural binomial. Let’s take the toilets of the MIAC – Castillo de San José as an example, whose windows allow us to see the sea and the vegetation outside. It seems as though urinating in this toilet (an artificial structure) is similar to doing so outdoors (surrounded by nature). Was he trying to offer a complete experience to the visitor, one that doesn’t end at the core of his works, but rather expands into the toilets?

In his spatial interventions, he presented a new way of creating and living. The search for an ideal type of architecture that would respect the landscape and fit within an economic context marked by tourist development led him to propose an approach without a written theoretical body, but with examples that are guided by three main principles: the conservation of nature, respect for the architectural tradition of the place, and the use of modern resources.

The combination of these major lines of action and the specificity of other more concrete characteristics resulted in works full of imagination and originality. In this architecture, we find a close affinity with the human condition, which has likely led to its immediate acceptance by those who visit it. The binomial of Art and Nature became his hallmark.